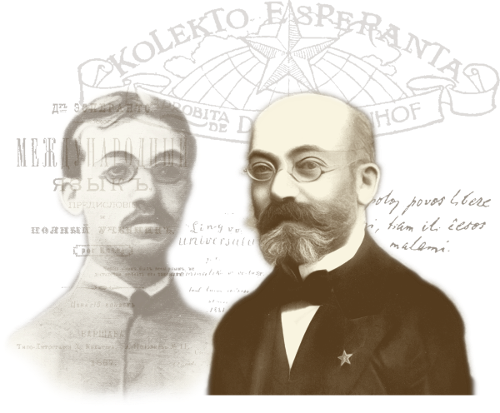

I recently spent several days attending to the English version of a biographical website about Ludovik Lejzer Zamenhof (Zamenhof.info). This started out quite simply as proofreading the original English translation, and making a few stylistic changes here and there. But as I worked my way through the site I found myself increasingly referring back to the original Esperanto, trying to make a better translation, and even adding completely new information.

The basics

Zamenhof was born in the town of Białystok in 1859 and moved to the city of Warsaw with his family at the time of his 14th birthday. Both are now cities in Poland, and were then cities in the Congress Poland district of the Russian Empire. The languages used in the family home were Yiddish and Russian, and other languages would have been widely heard in the wider community, especially Polish, but also German, Lithuanian, Romani and Ukrainian.

So, like many, Zamenhof was a polyglot from a young age, but more uniquely, from a young age he also dreamt of creating an international language. Something in a similar vein to Volapük, but more linguistically sophisticated. He finished his design of his ‘lingvo internacia’ in 1878, and after further refinements released the Esperanto project in 1887.

The first Universal Congress was held in 1905, and it went on to be an annual affair held in a different city each year. In the early 1900s Zamenhof sought to amalgamate Esperanto with a religious doctrine called Homaranismo/Hilelismo which he had designed, although this ultimately never took off in the Esperanto movement. He died in 1917.

‘A utopian project rooted in its imperial Russian milieau’ (quote from O’Keeffe 2019)

Esperanto, Hilelismo and Homaranismo were each attempts by Zamenhof to remedy sectarianism and to bring people together. But why did he see language and religion as the remedy?

‘As someone who was born and educated in the multi-ethnic Russian empire, Zamenhof was unaware of the level of linguistic heterogeneity in Germany, France and other western-European countries. Similarly, he did not fully realise that religion had lost its cardinal role in society. He therefore overly fixated upon language and religion, and overlooked how political, economic, and psychological factors also must be addressed to achieve the type of society which he desired.’ (source: https://zamenhof.info/en/idearo)

Although Zamenhof was an expert optometrist by trade, it does seem that he might have been somewhat blind to how a political and economical worldview would be required to bring about the post-sectarian paradise he dreamed of.

Trying times: Zamenhof’s Jewish identity

From his birth in 1859, Zamenhof’s life correlated with intensifications of anti-Semitism in the Russian empire. So he was conscious of his Jewish identity from a young age.

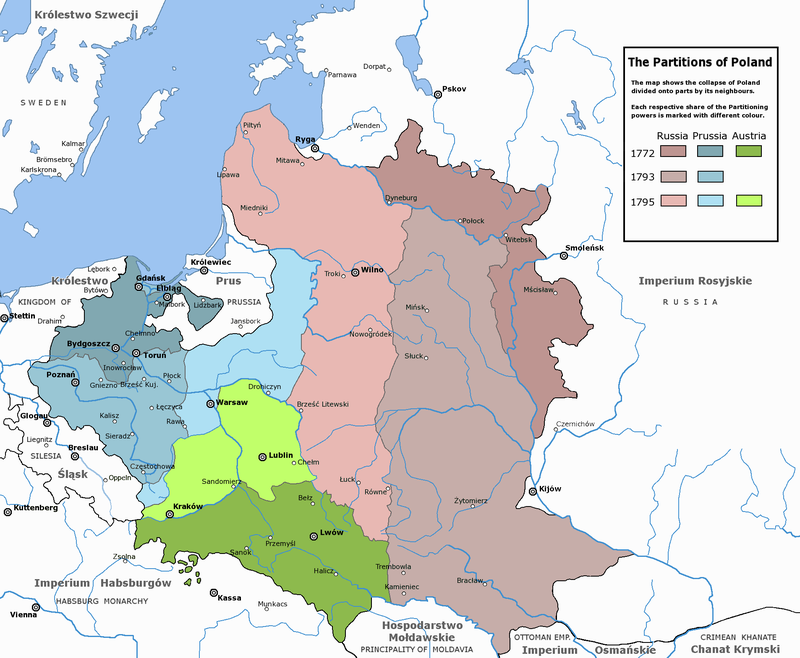

64 years before Zamenhof was born, in 1795, Poland lost its independence simultaneously to the Russian, Prussian and Austrian empires. The 1795 partitioning was the third and final wave of the partitions of the Polish state. Prior to then, there had been a Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and Poland had been an independent state power for around 800 years.

In January 1863, the underground Polish national movement rebelled against the Russian empire. The insurrection continued for a year and half, in alliance with the Garibaldi Legion from Italy. The Jewish denomination to which the Zamenhof family belonged, Litvak Ashkenazi, had strong links with Lithuania, where much of the population had been Polonized, and where the rebellion was centred (Korženkov 2009, chapter 2).

Squadron (attached) is a good film about the January Uprising. Within the first 10 minutes there is a scene extremely relevant to Jews.

However, the Zamenhof family did not take part in the uprising. This uninvolvement was not mere apathy, but rather stemmed from Zamenhof senior’s deliberate adoption of a Russian identity to assimilate and climb the social ladder (O’Keeffe 2019, 3-4). Zamenhof senior was rewarded for his loyalty to the Russian state, achieving work as a schoolteacher for the Russian state (Korženkov 2009, chapter 2). In 1873, the family moved from Bialystok to Warsaw; perhaps a sign of social mobility.

In 1879, Zamenhof moved back to Moscow to study medicine at the Imperial University there. Part of the reason why Zamenhof senior was so keen for his children to study is that Russian anti-Semitic laws did not apply to those Jews who had university degrees (O’Keeffe 2019, 4).

In 1880, Zamenhof junior finalised his modernisation project of the Yiddish language, a Germanic language which evolved among Jewish people in Europe (not to be confused with Hebrew, the Semitic language spoken by most Jews in Palestine/Israel). “He proposed the use of Latin characters and a new, rationalized orthography that would free Yiddish from German-influenced spellings. In terms of orthography, Zamenhof was ahead of his time, anticipating by decades both the Soviet reform of Yiddish orthography and the Latin transliteration conventions developed by YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in the 1920s” (Treger 2009). Nonetheless, Zamenhof’s proposals were not published until 1982 (Korženkov 2009, 11).

The anti-Semitic tensions in the Russian empire reached boiling point in 1881 following the March assassination of Tsar Alexander II in Saint Petersburg. This assassination was part of a proto-socialist political campaign which sought an end to the perverse inequality and backwardness of Tsarist Russia.

A film clip of the assassination scene from a historical fiction movie.

The ten assassins were all hung to death by the state. Only one of them was Jewish, and her role was greatly exaggerated in subsequent propaganda. In the aftermath of the assassination, Tsarist loyalists scapegoated the Jewish community. ‘One third will die out, one third will leave the country and one third will be completely dissolved in the surrounding population’ – Tsarist minister Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev.

Pogroms started in April 1881, and over three years more than 200 were carried out in the Russian empire. A pogrom is when racist thugs run amok violently attacking Jewish people. From 1891-1914, around 2,500,000 Jewish refugees fled Russia for western Europe and America. Zamenhof moved back to the family home and continued his studies in Warsaw from September 1881. His father could save money this way, and doubtless the family felt more comfortable all being together in a dangerous time. But pogroms also occurred in Warsaw: in December 1881, the Zamenhofs spent three days hiding in their cellar to stay safe (O’Keeffe 2019, 5).

Young Zamenhof ‘emerged from that cellar and channeled his outrage’ (O’Keeffe 2019, 5). In February 1882, he founded the Seerit-Israel activist group to raise money for the cause. In January/February, his series of articles ‘What, Ultimately, is To Be Done?’ were published in the Russian Jewish ‘Razsvat’ journal. It had become clear that the attempts of the Jewish people to self-assimilate had failed. He advocated the establishment of a Jewish homeland in North America, specifically on the virgin earth along the Mississippi river – not in Palestine as was actually done (O’Keeffe, 2019, 5).

‘Palestine was sacred to both Christians and Muslims, a place where religious belief ran high, and would place Jews in danger, sapping the resources with which they were to build a state. Palestine belonged to the Turks, who would not willingly surrender it. In short, it was an alien, inhospitable, and primitive place that promised hostility rather than peaceful coexistence’ (Treger 2009). Nonetheless, when his American proposal was met with ridicule, he acquiesced to the Palestinian plan, but only until 1887 when he renounced Zionism altogether.

The Jewish activists used Biblical codewords in their pamphlets to try and avoid censorship issues. For example, the pogroms were referred to as ‘the Storm in the Negev’, a reference to the Old Testament.

The situation was getting worse before Zamenhof’s eyes. In May 1882, the Russian state passed a series of new laws which specifically applied to Jewish people, restricting their freedom of movement and right to buy property. Even before these laws, Jews’ freedom of movement was already largely limited to an area called the Pale of Settlement. These were only done away with following the 1917 Russian Revolution.

In August 1883, Zamenhof co-founded the Warsaw chapter of Hibbat Zion (a forerunner of modern Zionism) and was also elected as the president of the Hibbat Zion national committee. He was tasked with establishing links with the Bilu activist group of Zionist Socialists, established 1882. Their aim was to settle in Palestine and Syria and many of them did just that. He looked forward to the end of 1884, because then he would graduate and could move to Palestine with his comrades.

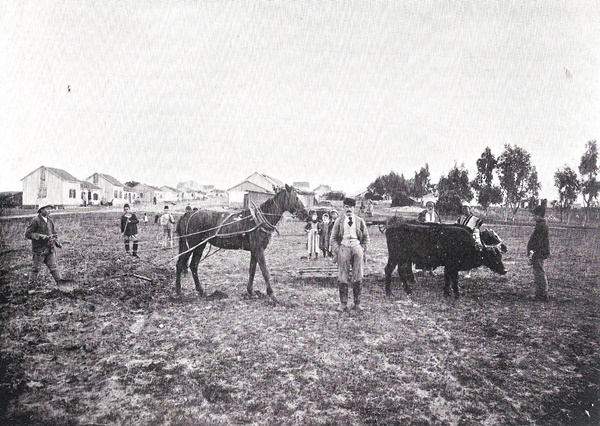

Early settlers in Israel. From http://www.zionistarchives.org.il/en/datelist/Pages/BenYehuda.aspx#!prettyPhoto

Early settlers in Israel. From https://israelforever.org/history/aliyah_bet/the_backdrop_of_jewish_settlement_the_early_aliyot/

But actually Zamenhof’s Zionist activism diminished. He did indeed move away from Warsaw early in 1885 after graduating, but only to Viesiejai (in Russian-controlled Lithuania) where he bided with his sister and her husband for a few months whilst working in a medical practice there. He moved a few more times; building his professional experience, and completing a Masters degree in Vienna; but he always lived in central and eastern Europe. He did leave Europe to travel to the Universal Congress in Washington DC in 1910, but he never went to Israel. Zamenhof rejected Zionism in 1887, however he always held onto his Jewish identity. Some of his family remained active Zionists (Korženkov 2009, 48).

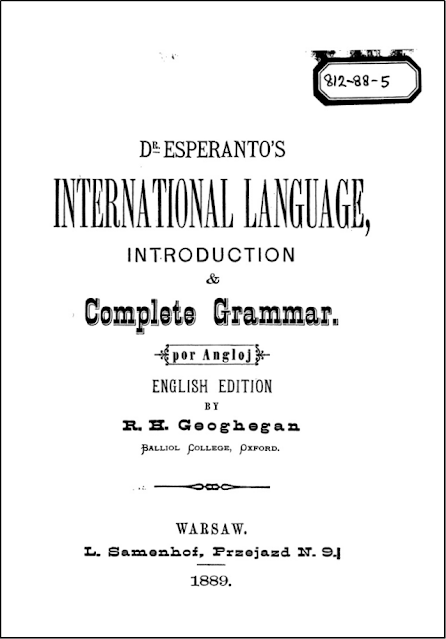

Zamenhof’s public denouncement of Zionism coincided with his marriage and with the publication of the first Esperanto book. This followed years of trying and was sponsored by his father-in-law.

A classic early English edition, translated by Irishman Richard Geohegan, following the first English version which was a botched job.

Although his Esperanto project was in large part a response to anti-Semitism, when Zamenhof published Esperanto, he did not mention Jewish issues. But once Esperanto had gained a following, Zamenhof opened up about his belief that Esperanto could be a solution to anti-Semitism and ethnic hatred (O’Keeffe 2019, 7).

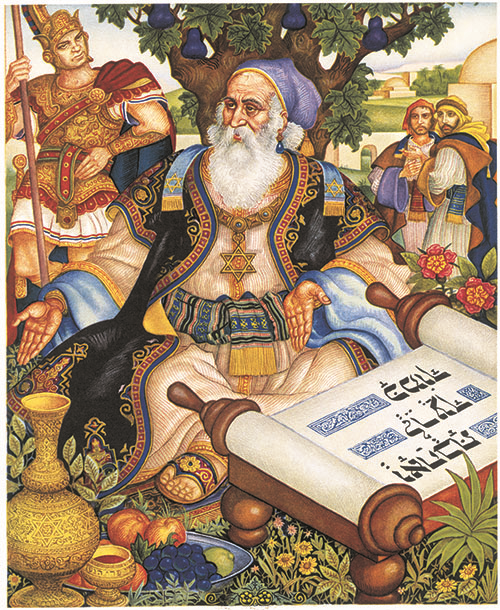

In fact, through his Hilelismo project, Zamenhof theologised Esperanto. He amalgamated his internationalism with the Jewish cause (not to be confused with the Zionism). The name referenced Hillel the Elder, a wise Jewish philosopher who had lived slightly before the time of Christ.

Portrait of Hilel the Elder by Arthur Szyk

As a translator of Zamenhof.info, I changed Hilel’s words ‘Do not do unto others what is hateful to you’ to Christ’s ‘Treat others as you would like to be treated yourself’. Most Anglophones will probably already know the Christian version, and its more understandable to English ears. But anyway, both versions are essentially just slightly different expressions of ‘the Golden Rule’, which has been expressed in many cultures.

At the time though, Zamenhof’s philosophy did not find much support. It was widely received as ‘just another -ism’. In fact, it was widely criticised for excessive idealism. During Esperanto congresses, Zamenhof was even pressured not to mention Hilelismo in case it provoked any anti-Semitism from Esperantists (Treger 2009; Korženkov 2009, 5; O’Keeffe 2019, 10). Zamenhof complied, and he instead spoke about the sectarian situation in rather veiled terms. Here are some excerpts from a speech he gave at the second Universal Esperanto Congress in 1906:

I come from a land where many millions of people are fighting with difficulty for their freedom, for the most elementary and human liberty, for the rights of man.

In the streets of the distressed city where I was born, men armed with axes and iron bars would throw themselves like cruel animals against peaceful citizens whose only fault was speaking another language and having another religion… they broke the skulls and poked the eyes out of women, frail old people and helpless children. I’ve said enough about the sick butchery that happened in Białystok. Just remember, fellow Esperantists, the walls among peoples are still high and thick, but we fight against those walls.

Our congress has nothing to do with political affairs.

Also, from 1912:

It is not necessary that every Esperantist becomes compelled by the internal idea of Esperanto. Nonetheless, the internal idea fully governs Esperanto congresses, and it must continue to do so. But what is the internal idea? That the fundamental linguistic neutrality of Esperanto can remove the cultural and language barriers between people and make Esperantists gradually recognise the humanity of people from other backgrounds, even the brother and sisterhood of all peoples. This will affect different people in different ways, an almost infinitely diverse variety of ways. An individual’s highly personalised response to the internal idea should not be confused with the internal idea itself.

[A note from me the translator: for example, somebody who belongs to a prestigious group in society may have a humbling experience, whereas somebody from background which is of lower status may find the experience deeply empowering].

Overly apolitical

In accounts of Zamenhof’s life in Russian-controlled Poland, there is a contrived non-political character. A picture is painted of all nationalities being as bad as each other. Russians, Poles, Jews, Lithuanians, Belarusians, Ukrainians, etc., all holding each other in mutual disdain.

But with the exception of Russia, these were each stateless nations, and the Russian state actively sought to assimilate these minority groups. It is perverse to equate (a) struggles from below to resist assimilation with oppression, with (b) persecution from above. The ordinary working-class Russians were not to blame; only the backwards imperialist tsarist regime.

In Zamenhof’s own words, from his address to the 1906 Universal Congress: ‘The Russian people are not to be blamed for the beastly massacres. The Russian people have never been cruel nor blood thirsty. Similarly, neither the Tartarians or Armenians can be blamed for the constant butchery which occurs in the Caucasus; both peoples are peaceful and do not wish to force their government upon anybody; the only thing they want is to be left alone to live in peace. Clearly, the blame is on a group of depraved criminals who, by means of different and dishonest maneuvers, widespread lies and artificial denigration, created hate among one people and the other.’

In short, and although Zamenhof was not quite so explicit, the elite Russian imperialists mercilessly executed a cold-blooded calculated divide and conquer strategy.

Tsar Nicholai II and Tsarina Aleksandra (ruled 1894-1917).

The working-class and socialist movement in Russia overwhelmingly supported the rights of self-determination of small nations, in accordance with the views of the Second International. With respect to the political spectrum, self-determination movements were generally situated left of centre. For example, Józef Piłsudski, the leader of the Polish independence movement, wanted Poland to be a multi-ethnic country where Jews could live comfortably. For more details see my articles (PL 1 + PL 2).

In February 1904, war broke out in the far east over the competing imperial ambitions of Russia and Japan. The Russo-Japanese war, which Russia lost, ended in September 1905 after 19 months. Overlapping with that war, a socialist revolution broke out in Russia in January 1905. It would go on for nearly 2.5 years. The Polish national movement – even those in Austrian and German held Poland – used this opportunity to fight against imperial Russia for independence.

It is recorded that this turmoil strengthened Zamenhof’s resolve to articulate his beliefs and ideas. Indeed, it was in this context that he published the second edition of Hilelismo in 1906, which was rebranded as Homaranismo that same year.

Its a great philosophy, but did it sufficiently grasp the situation in the required scientific sociological manner? As a translator, I found myself adding in terms like imperialism, class, nationalism and internationalism to the English version, which had not been in the original Esperanto writings. On one hand, my translation construed Zamenhof’s original message. But my intention was simply to try and bring clarity in the English version, which I do not think was there in the original Esperanto. Possibly because he did not enjoy freedom of the press on which more below.

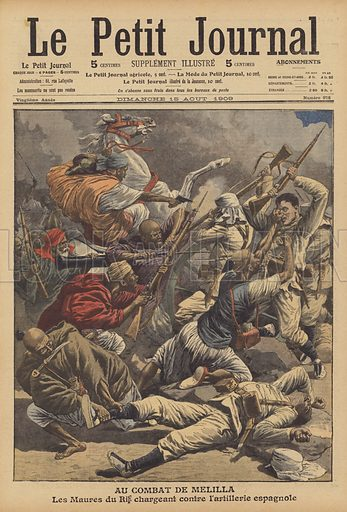

At the 1909 Universal Congress in Barcelona, Zamenhof frustrated many locals by accepting a knighthood from the Spanish king and by remaining silent on the dire political situation (Korženkov 2009,32). Spain was conducting an imperial colonial war in Morocco, and forcing ordinary people to fight in the war as conscript soldiers. This was part of the scramble for Africa between competing European empires. An organic working-class uprising occurred, but was brutally crushed by the Spanish state during ‘Tragic Week’. Over 100 civilians were murdered, 1700 were charged as criminals, 59 received life sentences. The brutality which these Catalonian martyrs sought to avoid in Africa was even worse. But Zamenhof steered clear of politics during his time in Barcelona.

Image from: https://www.lookandlearn.com/history-images/M512059/The-Second-Melillan-Campaign-Morocco

But as mentioned, omissions in Zamenhof’s writings may be partially attributed to a lack of freedom of the press. Each of his works had to be approved by the censorship board, who sometimes did not grant permission. For example, there are historical records that show that in October 1888 the state refused to permit the publication of what would have been the first weekly Esperanto journal. Perhaps Hilelismo was watered down in order to pass the censors. Zamenhof was also silenced over some issues due to peer pressure.

The usual story is that Zamenhof wrote under a pseudonym to avoid being seen by his clients as a dreamer preoccupied with unprofessional side issues; i.e he worried about his business taking a hit. I do not find this story convincing. His diaries show that he worried about his identity a great deal, and one wonders whether he was really worried about his business, or was perhaps more worried about physical harm coming from the state/racist loyalist thugs.

Indeed, I do not find the story about him worrying it would hurt his pocket particularly convincing; he deliberately lived a frugal, modest, altruistic lifestyle until his death. He was knighted by the French and Spanish empires, but chose to reside in a working-class part of Warsaw. He was a very highly qualified healthcare professional who ran an eye care clinic, but he kept his prices inexpensive in comparison to his competition. He would turn nobody away, often waiving the fees of clients who were evidently hard up. Due to the value for money which Zamenhof offered, he attracted a large clientele and in turn overworked himself.

He died in 1917 of a broken heart caused by the war. That # war to end all wars caused him great stress.

Lessons for the Esperanto movement in the here and now

On the one hand, considering the saint-like character of Zamenhof, it does not feel right to make any critique of him. On the other hand, Zamenhof explicitly and modestly stated that he left the Esperanto project unfinished. The ‘internal idea’ still presides over Esperanto gatherings. But we should remember that the internal idea was a watered-down version of what Zamenhof truly believed in; Hilelismo. And even Hilelismo, he may never have fully articulated due to censorship and peer pressure. But now is the time that the Esperanto movement must integrate Zamenhof’s omissions into the DNA of Esperanto.

The internal idea should become the external idea also. We must be more self-aware. More conscious of the objective circumstances which exist in society, and we must continually audit situations as they change over time. The ‘flower power’ good atmosphere of Esperanto gatherings is great. But it only lasts for the duration of the event. It is a temporary escape from reality, not an attempt to ameliorate society.

Esperantists should seek to represent Esperanto in a manner which will appeal to as many people as possible. ‘People’ does not refer just to Esperantists, but all people; there is little to be achieved from preaching to the choir. Led by the contemporary zeitgeist, we must make ourselves as accessible as possible. We should not just resign ourselves to accept the situation as we find it, passed down to us from previous generations. The way we represent ourselves now must be a manifestation of the ‘fina venko’ we dream of.

If the author of Esperanto was not born in Poland, he or she could quite easily have been born in Britain or Ireland, for example in Belfast, Derry or Glasgow. Perhaps as the child of Polish immigrants nowadays; or as a Gael pushed into an industrial city by invisible economic forces during the 1800s; or a Scot who moved to the north of Ireland on the command of the British emperor in the 1600s or 1700s. These retellings of Zamenhof’s life would allow us to explore the minority languages of these islands (Irish, Gaelic, Scots, etc); as well as to explore sectarian issues which are closer to home than 1800s Poland, rather than trying to use Esperanto as a carpet to sweep them under.

Who is going to organise the Esperanto youth movement in Belfast? Junularo Esperantista Brita has been dormant for some years now, and to my knowedge no similar group exists in Ireland. I have helped set up the Movado Junulara Skota (Scottish Esperanto youth movement; MoJoSa also means ‘cool’). It is not evident from our name, but we hope to revivify the Esperanto youth movement throughout Britain and Ireland more generally. So I think it would be a good idea if the Movado Junulara Skota was able to affiliate to some kind of new federally-organised umbrella group, something in the spirit of a ‘sennacia asocio tutbrita-tutirlanda’.

I propose the symbolic name ‘Junulara IONA’. IONA stands for Islands of the North Atlantic, i.e Britain and Ireland. Iona is also a beautiful Scottish island where St. Columba from Ireland commenced his Hiberno-Scottish mission in the year 563. For centuries there was a very international and multilingual Celtic monastery there. Now it is a place of ecumenism. So its quite a fitting name for our ecumenical movement.

Bibliography

- www.Zamenhof.info (solely under the auspice of UNESCO; realised by Education@Internet)

- Mikołaj Gliński (2017) Białystok: The Original Babel of the Eastern European Borderlands. Culture.PL. URL: https://culture.pl/en/article/bialystok-the-original-babel-of-the-eastern-european-borderlands

- Aleksandr Korzhenkov (2009) Zamenhof: The Life, Works, and Ideas of the Author of Esperanto. Esperantic Studies Foundation. Translated from Esperanto by Ian M. Richmond. URL: http://www.esperantic.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/LLZ-Bio-En.pdf

- Brigid O’Keeffe (2019) An International Language for an Empire of Humanity: L. L. Zamenhof and the Imperial Russian Origins of Esperanto. East European Jewish Affairs, 49(1): 1-19. URL: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13501674.2019.1618165 (requires university login).

- Pakn Treger (2009) Esperanto – A Jewish Story. Pakn Treger, Magazine of the Yiddish Book Center, 60(5770), URL: https://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/language-literature-culture/pakn-treger/esperanto-jewish-story

- Michael Vrazitulis. (2020) Pogroms against Jews, the emergence of Esperanto and the fate of the Zamenhof family. TEJO. In Esperanto with English subtitles. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Ur5RaY7rGY

One thought on “Exposing Esperanto’s hidden politics in the Zamenhof-era; and drawing lessons for Esperantists in the here and now”